-

Dubberly Design Office

2501 Harrison Street, No. 7

San Francisco, CA 94110 -

415 648 9799 phone

415 648 9899 fax

Articles

A taxonomy of models used in the design process

Models are increasingly important in design—as design, in collaboration with other disciplines, increasingly deals with systems and services. Many aspects of customer experience unfold over time and location, and thus are intangible. With their ability to visualize and abstract various aspects of a given situation, models become tools for exploring relationships in ways that aren’t otherwise possible. To this end, models are able to synthesize different types of data (qualitative and quantitative), as well as inputs from various perspectives to provide visibility into issues occurring at the boundaries of disciplines. Where differences in discipline language, practices, and approaches can get in the way of problem solving, models can provide insights and frame discussions that must take place.

A Proposal for the Future of Design Education

*Submitted as input for the update of the Design Education Manifesto, ICOGRADA, March 28, 2011*

In 2000, the International Council of Graphic Design Associations (ICOGRADA) published their first “Design Education Manifesto,” noting “many changes” in design practice, defining “visual communication designer,” and suggesting “a future of design education.” The ICOGRADA manifesto marked a turning point—an international design body addressing change at the millennium. Publishing the manifesto was a significant accomplishment. A decade later, ICOGRADA are updating their manifesto. This essay responds to their request for input.

How the Knowledge Navigator video came about

Sparked by the introduction of Siri, as well as products such as iPad and Skype, there have been many recent posts and articles tracing the technologies back to a 1987 Apple video called “Knowledge Navigator”. The video simulated an intelligent personal agent, video chat, linked databases and shared simulations, a digital network of university libraries, networked collaboration, and integrated multimedia and hypertext, in most case decades before they were commercially available. Having been involved in making Knowledge Navigator with some enormously talented Apple colleagues, I thought I would correct the record once and for all about what really happened:

Convergence 2.0 = Service + Social + Physical

*Written for Interactions magazine by Hugh Dubberly.*

In 1980, when I was a college student, I heard Nicholas Negroponte speak about the future of computing. What stood out most was his model of convergence. Negroponte presented the model in three steps. The first slide showed the publishing, broadcasting, and computing industries as separate rings; the second slide showed the rings beginning to overlap; and the third slide showed the rings almost completely overlapped. The publishing, broadcasting, and computing industries were converging and would soon become one.

Convergence 1.0 = Publishing + Broadcasting + Computing.

Conversational Alignment

*Written for Interactions magazine by Austin Henderson and Jed Harris.*

People invent and revise their conversation midsentence. People assume they understand enough to converse and then simply jump in; all the while they monitor and correct when things appear to go astray from the purposes at hand. This article explores how this adaptive regime works, and how it meshes with less adaptive regimes of machines and systems.

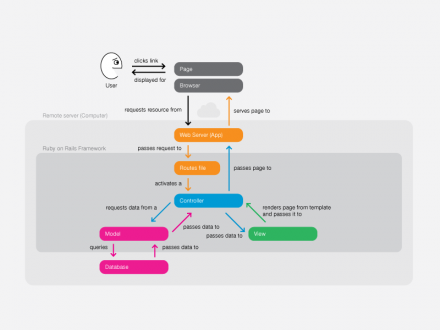

A Model of the Operation of The Model-View-Controller Pattern in a Rails-Based Web Server

This article examines The Model-View-Controller Pattern in a Rails-Based Web Server.

Imagine Design Create

Interview with Hugh Dubberly

—–

A design innovator argues that design learning is a prerequisite for design thinking.

**You have said that design is stuck. What do you mean?**

Design practice does not learn. As a profession, we don’t even know how to learn.

Design as Learning—or “Knowledge Creation”—the SECI Model

Written for Interactions magazine by Shelley Evenson and Hugh Dubberly.

Design

Designers often speak of design as a process. Typically, design thinking leads to design making, which leads to artifacts. Yet the design process also leads to something more—to new knowledge. Thus, we might characterize designing as a form of learning.

Curiously, the converse is also true. We might characterize learning as a form of designing. That is, the process of observing, reflecting, and making (and iterating those steps) may aid learning. Several designers and teachers have recognized the link between designing and learning and are bringing designing into curricula not just in college but also in high school and even elementary school. See, for example, a recent New York Times article, “Putting New Tools in Students’ Hands” [1].

More…Ability-centered Design: From Static to Adaptive Worlds

*Written for Interactions magazine by Shelley Evenson, Justin Rheinfrank and Hugh Dubberly.*

*Editor’s Note:

*

*After a long career in systems engineering and design, John Rheinfrank died on July 4, 2004.

*

*John’s Ph.D. dissertation explored what he called “organic systems theory,” or what’s now called “complex adaptive systems”—bridging multiple disciplines and theoretical frames (e.g., biology, computing, economics, psychology, and sociology). John spent most of his professional life applying principles derived from living systems to designing systems for people—from design languages that could serve as the foundation for a broad range of reprographic machines for Xerox, to personal information and communication appliances for Philips. In essence, he wanted us to design systems that are alive.*

*In the years since John’s death, complex systems have become deeply engrained in our everyday lives, from Facebook and Twitter to the interconnected financial systems that plunged us into the credit crisis. When John learned he was sick, he began working on a book on the relationship between design and systems. Sadly, he never finished, but some of his core ideas were preserved in a presentation on moving from static to adaptive worlds. John saw adaptive worlds as a new way to frame interaction design, which makes it an important topic for interactions. This presentation was his way of helping us make the leap from the present to the future he could already envision. Working from John’s presentation slides and a tape of his talk, we have summarized his ideas.*

*—Hugh Dubberly*

The Space of Design

Models of the process of design are relatively common. (I have found about 150 such models, many of which are presented in How Do You Design?) Each describes a sequence of steps required to design something—or at least the steps that designers report or recommend taking. Models of the process of design are common because designers often need to explain what they do (or want to do) so that clients, colleagues, and students can understand.